A Deep Dive into a Shallow Lake: The Disappearance of the Aral Sea

The once-vast Aral Sea has all but vanished. In this article, we explore how ideology and power helped create a textile industry so thirsty that it threatens the survival of a whole region.

The Aral Sea was once the fourth largest lake on Earth, sprawled across swathes of desert shared by modern day Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan. Over millennia, climatic fluctuations and temperamental tributaries have caused the sea to shift in size. Since the 1960’s however, the lake has all but disappeared. This time, the shrinking doesn’t owe to the slow march of natural environmental change, but to deliberate, extensive human activity. Swallowed up by a thirsty cotton industry, the lake’s eradication has ravaged the local ecology, and the human population depending on it.

Named amongst the ‘worst environmental disasters’ by former United Nations Secretary General Ban-Ki Moon, the crisis has its root causes in the unslakable thirst of industrial cotton production. Pursued by the Soviet Union as a means of self-sufficiency, and leap towards modernity, the environmental exploitation has been perpetuated since the 1990s by global markets and corrupt officials. The ill fortune of the Aral Sea, its human, and non-human populations, serves as an instructive example of the resource-hungry, ecologically-ravaging power of industrialised cotton production.

Before exploring the causes of the crisis, it is worth outlining what the Aral’s disappearance has meant for the region. The scale of its reduction is extreme: the shoreline has receded by up to 100km in places, and the water level has dropped by up to 25m in others. Once half the area of England, the lake’s size has decreased by 60%. The immense reduction in water has had devastating impacts on the local ecology. Between 1961 and 2007, what remains of the lake has increased in salinity by a factor of ten, which has led to the extinction of the Aral Salmon, as well as the decimation of other aquatic life. Similarly, the literal disappearance of the lake has reduced breeding and feeding areas for fish. Across the basin, endemic vegetation has been replaced by salt-loving plants, and swathes of land have become uninhabitable, salt-marsh solonchak. Only half of local animals and bird species remain.

These changes don’t solely stem from diminishing freshwater input, but also due to the amount of industrial irrigation runoff generated by cotton production. Pesticides, herbicides and chemicals used in the cotton harvesting process have destroyed wildlife, and are linked to cancer in humans. It is here where we see the crucial links between environment, society, and politics: the Aral Sea disaster is not simply a sentimental mourning of the destruction of an environment, but illustrative of the unshakeable dependence on nature that humans have.

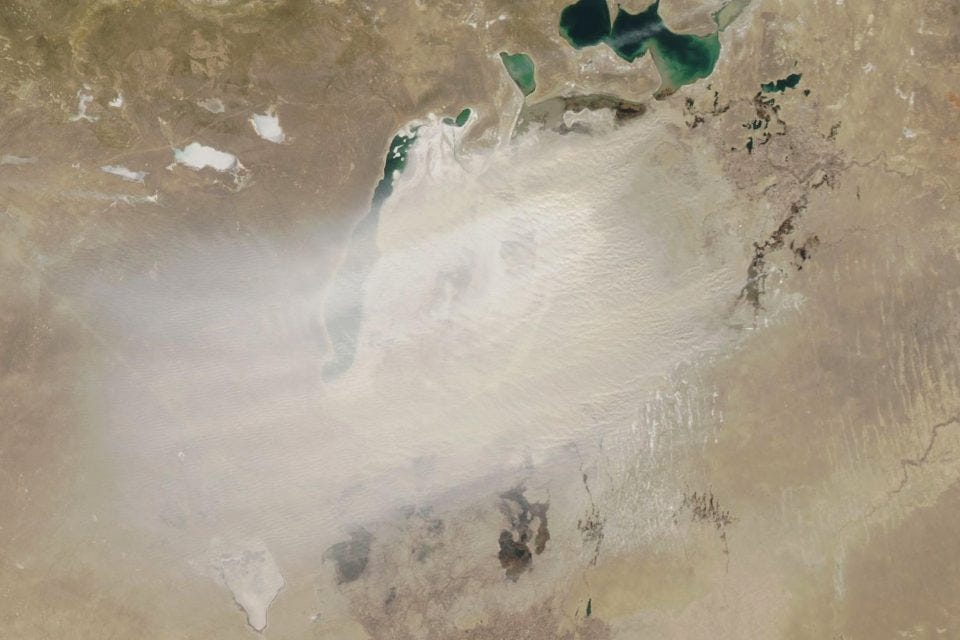

The communities of the Aral basin have had to watch their livelihoods literally run away from them, the retreating shoreline taking with it the lifeblood of the region: fishing. Today, the port town of Moynaq is divorced from the sea, the coastline some 60 miles away. Poignant images of stranded fishing boats, sat absurdly in a sea of sand like erratics in a desert, reflect the extent of the changes. The nutritionally rich lake has been replaced by barren desert plains, and the once-fertile fields of the river deltas have also been starved of water and nutrients, meaning that the deficit in aquatic protein has been difficult to replace with agriculture. It has also been harder for locals to rear livestock, as edible plants make way for woody and nutrient-poor salt-loving vegetation. Vast dust storms, amplified in severity and frequency by the increase in exposed lake bed, scour the surface, propelling natural salts and agricultural chemicals into the air. These storms make farming even harder, and exacerbate respiratory illnesses in humans.

The infant mortality and tuberculosis rates in the area around the Aral Sea are 3-4 times higher than those in the former Soviet Union. In 2001, Médicins-Sans-Frontières found that acute respiratory issues comprise over half of infant deaths in the area. Amongst the toxic chemicals leached from cotton production and found in the area is 2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (helpfully shortened to TCDD). This is chemically similar to the Agent Orange biological weapon used by the US Army to decimate Vietnamese food supplies during the war, and its concentration is stronger in the Aral basin than anywhere else on earth. The impacts of the Aral Sea disaster on health and livelihoods paint a troubling picture for industrialised textile production: through political choice, ecosystems have been destroyed, the humans dependent on them not just impoverished, but slowly killed by the toxic footprint of the cotton industry.

The disastrous effects of the sea’s waning have been brought about by decades of ecologically-irresponsible policy. As early as the October Revolution, Vladimir Lenin prioritised the implementation of industrial agriculture and cotton production to support the socialist project. Following the economic and demographic fallout of World War II, Stalin sought to make the USSR’s economy independent. This involved ramping up the production of ‘white gold’, a moniker for cotton that shows the plant’s vitality for the nation. CIA documents from the 1950s reveal that the Americans were keeping a watchful eye on the surge in Soviet cotton production. A USSR-wide process of mass industrialisation, adherent to centralised directives, ensued. Stalin launched a quintessentially Soviet ‘Great Plan for the Transformation of Nature’, designed to improve agricultural productivity across the USSR. After his death, Krushchev and Brezhnev continued to support the industrialising drive across Central Asia.

The Aral Sea’s tributaries, the Syr Darya and Amu Darya, were gradually dammed and re-routed, their waters desired for irrigating vast plantations. Between the 60s and the 80s, Uzbek cotton plantation acreage increased by over 50%. At its peak, 1.47m hectares of land were producing cotton. Single most destructive to the delicate ecology of the Aral Sea was the construction of the Karakum Canal - a 1,300km long, man-made artery that fed the beating heart of Soviet cotton production. By the time of its construction, the volume of water reaching the Aral Sea was virtually nil. This intensive industrialisation was seen as necessary for the USSR to become economically independent, raise foreign currency, and also to literally put clothes on its people’s backs.

As early as the 1950s, there was some awareness of the risks of the irrigation project, but it is unclear whether these were unknown to, or ignored by, the Soviet bureaucrats. What is clear is that the value of one cubic metre of river water was considered much greater fuelling cotton production than it was keeping the Aral Sea and its ecosystem alive. This stubborn focus on textile production, underpinned by a Promethean belief in modernity and industrialisation, exposed a hierarchy of political prioritisation, which relegated nature - and the local peoples whose lifestyles depended on it - below the wellbeing of the Soviet whole. Traditional practices of water management and crop rotation, which allowed generations to live within the ecological bounds of the Aral Sea, were replaced by industrial monoculture at the behest of the centralised state.

The environmental and social consequences of this shift are unambiguous. But why did the Soviets pursue such a destructive policy in the region? James Scott’s seminal book Seeing Like A State may provide some insight. For Scott, the distinguishing feature of the nation state is a desire to impose rationality and order on society, and on nature. In the case of the Aral Sea, the ‘high-modernist’ values of the Soviet leadership created authoritarian, top-down policies that ignored local insights and the fragility and interdependency of the ecosystem. It was this obsession with ‘modern’ values that led to the cotton-above-all-else mindset that has caused the Aral Sea disaster.

Clearly, the metropole - that is, the seat of Soviet power to which Central Asia was peripheral - oversaw the incorporation of natural capital (i.e., land, water, nutrients) into the broader economy. Far from the more egalitarian ideals of socialism, the process of collectivisation - whereby farms were set directives by a central authority - led to hierarchical and uneven property relations. For Maya Peterson, the ‘success’ (in economic terms) of the cotton-producing project was not a triumph of high-modernist planning or technological development, but rather of violent coercion over collectivised labour. The Soviet strategy was “transforming people through transforming landscapes”(pp318). In other words, the centralised desire for industry was underscored by a belief that this would bring modernity to the far-flung peripheries of the Aral Sea. Even when Uzbek cotton was thriving, it was sold cheaply through the state-run schemes of the USSR and overseen by corrupt officials, with locals losing out again.

The collapse of the Soviet Union did little to help the situation. The local populations went from peripheral to the Soviet project, to peripheral populations of the newly-formed ‘Stans’, states which themselves were peripheral to a globalising economy. Whilst independence freed cotton production from the quotas set by the USSR’s bureaus, it brought about the exposure of the central Asian states to global markets. Reliant on earning foreign currency, it is no surprise that there was little political appetite to dismantle the exports of cotton that economies were dependent on, and in doing so pave the way for a recovery of the Aral Sea. In fact, cotton export dependency has actually increased since the collapse of the USSR.

The state-operated contemporary cotton industry of the Aral basin still involves environmentally destructive processes and chemicals, but a lack of financial incentive, political negligence, and capital is arresting the introduction of cleaner production. Evidently, the epochal shift between socialist member state, to an economically ‘liberalised’, capitalist country, has changed little for the fortunes of the Aral Sea. The nation-building motive may have been replaced by a profit motive, but subjugation of nature is the common denominator. Uzbek people continued to suffer under the resource-hungry, exploitative cotton industry. Children, teachers, and more are regularly put to work during the harvest season, disrupting education and under coercion of job loss. These seasonal workers are paid a pittance, pressured to meet government quotas and to enrich the select few who own the cotton plantations: in 2013, thirteen Uzbeks died in the cotton harvest. Global players in the fashion industry, fuelling the Aral Sea’s demise with purchase orders for cheap cotton, have been pressured into boycotting Uzbek produce since 2007. Following a decade-long boycott from the Cotton Campaign, there are tentative signs that the industry’s social conditions are improving.

In sum, there is no way to square maintained cotton production with ecological rejuvenation. In other words, the restoration of the Aral Sea is made impossible by the continued existence of industrial cotton production, and its intense hydrological needs. Given the extreme economic dependency of the local and national economies, the industry is off limits. Dismantling the industry to ‘save’ the sea would only harm the livelihoods of many Uzbeks and Kazakhs, who have been weaned onto ‘white gold’ by successive state regimes. These people have been exposed to the cotton industry: not just economically exposed, but also physically exposed to the toxins, extinctions, and social reorganisation that industrialisation has caused.

Only technological enhancements, the adoption of more sustainable techniques, and the introduction of more secure labour conditions can potentially ease the malaise of the region. The fate of the Aral Sea illustrates humanity’s uncompromisable dependence on healthy ecosystems, as well as how industrial production can upend large regions. As Uzbek cotton makes its way abroad to Bangladesh, and China, it becomes part of a growing fashion industry with greater material demands than ever. Fast fashion’s drive to increase consumption, and lower costs fuels the cotton industry’s appetite for natural resources. Just as the Soviet ideologues were unaware of, or unwilling to, protect the Aral Sea, one wonders how the investors of textile capital across the world may be ignoring the same warning signs, condemning environments and populations to similar cotton-ravaged futures.

Though the situation may seem terminal, not all hope is lost. Efforts have been made by a range of governments and organisations to reverse the damage to the Aral Sea: for example, the construction of dams, and the separation of the sea into distinct lakes. By focussing on the North Aral Basin, schemes have slowly managed to increase fish stocks through desalination, and frugal limits on fishing catch. Recovery is slow-paced, but small interventions that account for economic and ecological sustainability offer a chance for small steps towards more equitable, sustainable ecosystems, for people and the planet.

Aladin, N.V., Plotnikov, I.S., Micklin, P. and Ballatore, T., 2009. Aral Sea: Water level, salinity and long-term changes in biological communities of an endangered ecosystem-past, present and future. Natural Resources and Environmental Issues, 15(1), p.36.

Banyan, 2013. In the land of cotton The Economist. Available at: https://www.economist.com/banyan/2013/10/16/in-the-land-of-cotton (Accessed: 4 December 2023).Brain, S., 2010. The great Stalin plan for the transformation of nature. Environmental History.

Djumaboev, K., Anarbekov, O., Holmatov, B., Hamidov, A., Gafurov, Z., Murzaeva, M., Sušnik, J., Maskey, S., Mehmood, H. and Smakhtin, V., 2019. Surface water resources. In The Aral Sea Basin (pp. 25-38). Routledge.

Environmental Justice Foundation, 2010. White Gold: Uzbekistan, A Slave Nation For Our Cotton? Available at: https://ejfoundation.org/resources/downloads/ejf_uzbek_harvest_WEB.pdf (Accessed: 5 December 2023).

Hoskins, T., 2014. Cotton production linked to images of the dried up Aral Sea basin. The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/sustainable-fashion-blog/2014/oct/01/cotton-production-linked-to-images-of-the-dried-up-aral-sea-basin (Accessed: 4 December 2023).

McCannon, J., 1997. Positive heroes at the pole: Celebrity status, socialist-realist ideals and the Soviet myth of the Arctic, 1932-39. The Russian Review, 56(3), pp.346-365.

Micklin, P., 2007. The Aral sea disaster. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci., 35, pp.47-72.

Micklin, P.P., 1988. Desiccation of the Aral Sea: a water management disaster in the Soviet Union. Science, 241(4870), pp.1170-1176.

Peterson, M.K., 2019. Pipe Dreams: Water and Empire in Central Asia's Aral Sea Basin. Cambridge University Press.

Usmanova, R.M., 2003. Aral Sea and sustainable development. Water Science and Technology, 47(7-8), pp.41-47.

Scott, J. C., 1998. Seeing Like a State. Yale University Press.

Spoor, M., 1998. The Aral Sea basin crisis: Transition and environment in former soviet Central Asia. Development and change, 29(3), pp.409-435.

Springer. Chronology of the Aral Sea Events from the 16th to the 21st Century.

Whish-Wilson, P., 2002. The Aral Sea environmental health crisis. Journal of Rural and Remote Environmental Health, 1(2), pp.29-34.

Wheeler, W., 2018. Mitigating disaster: The aral sea and (post-) soviet property. Global Environment, 11(2), pp.346-376.

https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg12416910-800-soviet-cotton-threatens-a-regions-sea-and-its-children/

https://britishseafishing.co.uk/the-disappearing-aral-sea/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uzbek_cotton_scandal

https://www.rbth.com/arts/history/2017/08/02/how-cotton-led-to-the-collapse-of-the-soviet-union_815454

https://karakalpak-karakalpakstan.blogspot.com/