Resistance in Woven Form: The history and symbolism of the 'keffiyeh'

For our first article, we'll be exploring the history, symbolism, and the changing significance of the iconic Palestinian garment, from humble headscarf to emblem of liberation.

Welcome to Warp + Left! For the very first article, I will be looking into the history and significance of the Palestinian keffiyeh, the simple cotton headscarf that has arguably become the defining icon of the liberation movement. The recent wave of bloodshed in the Levant has sparked international outcry from many, whilst also exposing an ugly indifference towards colonialist violence, Islamophobia, and anti-Semitism amongst even the most widely-respected of Western institutions. It is against this backdrop that the story of the keffiyeh seems relevant.

But why fashion? It is a topic that may seem trivial against the backdrop of the appalling violence that is happening not just in Gaza and the Levant, but also across the Sahel, and in more inconspicuous, slow forms the world over as the climate crisis deepens. Firstly, I hope to convey how fashion is as much an industry as an art form, and a deeply exploitative and dirty industry at that. The discussion around ‘sustainable’ fashion must involve a deeper engagement with the political and material realities of an industry bigger than the catwalk; one that is worth trillions, and employs millions the world over. Secondly, I hope to connect fashion as a form of personal expression to broader trends and theories in ecology, sociology, and politics. You’d be hard-pressed to find something more ‘everyday’ than clothing, and by weaving these insights into the actual, physical fabrics you wear, I hope to make the politics of the fashion industry almost tangible.

Now, onto the keffiyeh. Also known as a shemagh, the keffiyeh is a large square cloth usually made from cotton, and adorned with repeating motifs. In a region of the world where things are incomprehensibly old, the particular origins of the keffiyeh are unsurprisingly blurred; its name is thought to derive from the Iraqi town of Kufa. Found throughout the Arab world most commonly in striking red and white, the keffiyeh is thought to date back to Sumerian times, where it denoted the status of its wearer. In the sunbaked, dusty deserts of the Arabian Peninsula, it also serves a very practical purpose, and has been worn by Bedouin, farmers, and soldiers alike for generations. On the website for the Hirbawi company - the last remaining manufacturer of the keffiyeh in Palestine - a full twenty uses of the cloth are listed, from dust protector, to water filter, to makeshift sling. Indeed, many militaries - including the British Army- have adopted the keffiyeh as standard uniform for warmer climes.

Beyond its functionality, the garment retains its formal status: it is still custom to don a keffiyeh when meeting a high-ranking official in Saudi Arabia and in Jordan.

Unlike the pan-Arabian red and white pattern, the Palestinian keffiyeh has its own distinct, monochromatic pattern. Its significance and identification with the Palestinian cause dates back - by most accounts - to the 1930s, and the revolt against the British mandate. Led by farmers with heads clad in black and white keffiyeh, the cloth became synonymous with peasant-led resistance against British rule, and against the influx of European Jews fleeing an increasingly dangerous, anti-Semitic continent. The Revolt would not lead to an independent Palestine: it is estimated that a tenth of working age Palestinian men were imprisoned, exiled, injured, or killed. The subsequent British withdrawal left behind a state of chaos, from which contemporary Israel emerged. Determined to create a homogenous ethno-state as a defence against almost a thousand years of persecution in Europe, the Zionists wrested control of the region. For historian Rashid Khalidi, Palestinians were the victims' victims: dispossessed by the Zionists, who were in turn victims of a millennium of European anti-Semitism. Nonetheless, the specifically Palestinian keffiyeh became synonymous with a specifically Palestinian identity as a result of the ongoing conflict.

Two figures were particularly key to the transformation of the keffiyeh into an internationally recognisable icon. The first was Leila Khaled, a militant member of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, a revolutionary socialist party that continues to exist today. Notoriously, Khaled was the first woman to hijack a plane: successfully rerouting a plane to Damascus in 1969, and being apprehended whilst attempting a similar feat the following year. Her reputation is unsurprisingly ambivalent - her status as gun-toting, freedom-fighter has earned her idolisation from many as a prototypic female revolutionary, but her violent actions have equally bestowed her the title of terrorist, which some in the Palestinian community lament for its impact on the international perception of their cause. Nonetheless, her position as a figurehead of revolutionary politics is undeniable. Famously, her lionised status was cemented when she was photographed during the hijacking, grinning like a Cheshire cat and wielding an AK-47. Of course, she was wearing - hijab-style - a keffiyeh.

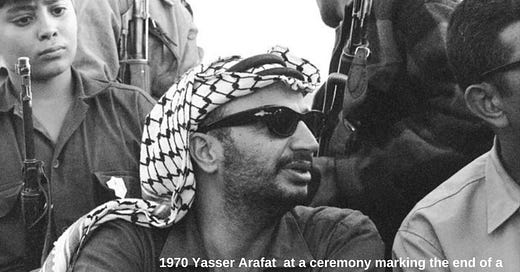

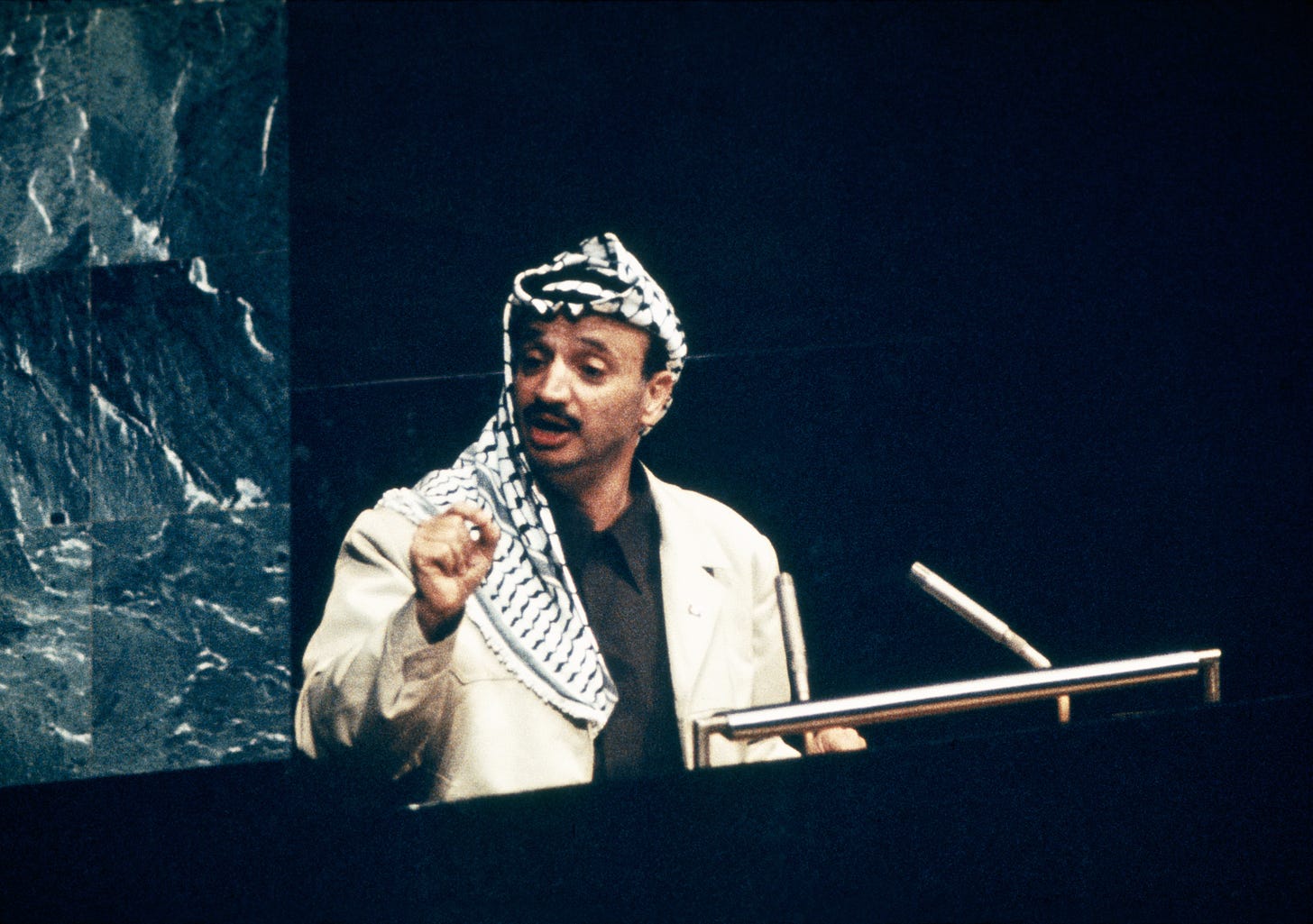

The other figure arguably most responsible for the proliferation of the keffiyeh is Yasser Arafat - founder of Fatah and one of the most influential figures in 20th century Levantine politics. Starting his career with a firm belief in militancy, Arafat was at the centre of the tumultuous Six Day War, and the surrounding conflicts of the 1960s and 70s. He was synonymous with the keffiyeh, pairing it with military fatigues whilst at the UN, and rarely photographed without one.

Later in his career, Arafat pivoted towards a more conciliatory diplomacy, pursuing a two-state solution in a moment of rare togetherness with his Israeli counterpart, Yitzhak Rabin. In the contemporary context of ongoing occupation, Hamas’ deplorable October 7th attack, and the subsequent Israeli military campaign on Gaza, the epochal handshake shared by Arafat and Rabin outside the Oval Office seems increasingly irrelevant.

The significance of the keffiyeh doesn’t simply lie in its co-option by various factions of the Palestinian cause, but also in the literal symbolism woven into its designs. The traditional keffiyeh has three repeating motifs, each deeply symbolic, and perhaps taking on a more tragic metaphorical significance as the situation in Gaza and the West Bank continues to deteriorate.

The chain-link pattern in the centre of the conventional keffiyeh is representative of the Palestine fishing tradition. Originally a celebration of the industry, and the natural bounty of Palestinian waters, the fishnet pattern has taken on an increasingly repressive quality. As the boundaries between Palestine and Israel have shifted over the last 6 decades, the Gaza Strip has become the last piece of Palestine connected to the sea. Unsurprisingly, fishing has become much harder for Palestinians, and the Mediterranean has become heavily militarised. US warships and the Israeli Navy prowl the coastline, and incidents with Palestinian fishing craft are frequent. Confiscated boats, export embargoes, a naval blockade, and the (sometimes realised) threat of being fired upon has become the contemporary experience of many a Palestinian fisherman. Marine access to the Gaza Strip is fiercely contested, as it has served as a route for weapons smuggling by allies of Hamas and other militant groups. In these conflict-ridden waters, it is local fishermen and the people who depend on their catch who lose out. In a region where food insecurity is rampant, and stockpiles virtually non-existent, the history of pride in a fishing industry woven into the pre-eminent Palestinian garment tells a sad story of decline and dispossession.

The same can be said of the thick square border that runs around the fishnet pattern. These bars are said to represent Palestine’s location as a locus of ancient trade routes of material and cultural exchange. Today, however, the free passage of goods, and most importantly people, is a myth to Palestinians. Oxfam has estimated that less than a fifth of the resources required for an adequate water infrastructure make it past the blockade. Residents of Gaza and the West Bank have extremely limited ability to move freely. Hemmed in by heavily militarised borders, there is little scope for the trade and mobility celebrated in the keffiyeh to be experienced by Palestinians today. It is not just the literal freedom to move that has been compromised, but also the aspects of mobility conferred by one’s citizenship. Arabs in Israel are technically full-fledged citizens, but their day-to-day experience is often a different story. Several laws have been passed in the Knesset over the years that hamper Arab rights: for example, ambiguous ‘social suitability’ criteria can allow communities to veto applicants for residents, drawing criticism from Human Rights Watch amongst others as a form of housing segregation.

These issues of movement and habitation have also come to redefine the final motif of the keffiyeh: the olive branch. The olive branch - the outgrowth of a hardy and long-living tree - is synonymous with the region, and is globally recognised as a symbol of peace, perseverance, and resilience. Literally and figuratively rooted to the land, the olive branch also serves as a stark reminder of the dispossession endured by the Palestinian people over the last 70 years. Starting with the Nakba (Arabic for catastrophe), wherein over 750,000 Palestinians fled the borders of modern-day Israel, the story of the region is one of displacement and dispossession. In the years since the Nakba, the Israeli state has annexed swathes of land in the West Bank, leading to an increasingly disjointed, leopard-print map of Palestinian enclaves, and occupied areas. Whereas Israeli settlements are provided with military support and resources by the state, Arab-majority villages are met with bulldozers and eviction permits. Olive groves in the West Bank have been repeatedly confiscated, burnt, or swallowed up into ‘sterile security zones’. In wondering why the keffiyeh is so meaningful, a more powerful metaphor is hard to imagine.

The keffiyeh is worn with pride by many Palestinians, as well as an increasing solidarity movement, evidenced by a vast groundswell of popular protests. Look amongst the bold reds, whites, and greens of these marches, and you will see the fishnets, borders, and olive branches of the keffiyeh. The material metaphors of the garment are ever-more reflective of the injustices and violence perpetrated against Palestinian people not by Jews, but specifically by an authoritarian, extreme government emboldened by the military-industrial complexes of the USA and the United Kingdom. In amongst the threads of the cloth, the story of occupation, and dispossession is pronounced, but so too is the struggle for peace and freedom.

P.S. Click Here to buy a keffiyeh from the Hirbawi factory in Hebron!

P.P.S. Since I started researching and writing this article, 3 Palestinian men were shot in Vermont. They were identified and targeted because they were wearing keffiyeh, and speaking Arabic. This horrific hate crime shows why it is important that we understand symbols like the keffiyeh, which can be misinterpreted and drive people to commit extreme acts of terror.

Bibliography:

https://fashiontrustarabia.com/a-symbol-of-resistance-the-rich-heritage-of-the-keffiyeh/

https://kuvrd.ca/blogs/blog/the-history-and-evolution-of-the-keffiyeh

https://originalkeffiyeh.com/blogs/hirbawi-blog

https://www.middleeasteye.net/discover/palestine-keffiyeh-resistance-traditional-headdress

https://www.holylanddates.co.uk/blogs/blogs/palestinian-keffiyeh-a-complete-guide

https://handmadepalestine.com/en-gb/blogs/news

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Palestinian_keffiyeh

https://images.dawn.com/news/1192086

https://www.hrw.org/news/2011/03/30/israel-new-laws-marginalize-palestinian-arab-citizens

https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/05/12/israel-discriminatory-land-policies-hem-palestinians

https://www.oxfam.org/en/timeline-humanitarian-impact-gaza-blockade

https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2008/sep/22/fashion.middleeast

Khalidi, W., 1988. Plan Dalet: Master plan for the conquest of Palestine. Journal of Palestine Studies, 18(1), pp.4-19.

Great article cleverly relating fashion to history and geography. Looking forward to more from you!

Excellent, especially about the tragic symbolism woven into the cloth. Thanks for gathering all that extensive research