Riches from Rags: A Short History of the Bangladeshi Garment Industry

For a country that has only been independent for fifty years, the growth of Bangladesh's garment industry has been nothing short of mind-boggling. Today we chart the development of this huge industry.

Bangladesh is the second-largest producer of ready-made garments in the world, only surpassed by the behemoth that is China. Yet no more than five decades ago, its industry was practically non-existent, and the country a ‘basket case’ (in the words of the not-so-dearly-departed American war hawk Henry Kissinger). Although cotton and jute mills peppered the flatlands of the Bay of Bengal, these vestiges of the East India Company’s presence had fallen mostly silent. How, then, did a thriving, globally important garment sector emerge, and become the country’s dominant industry?

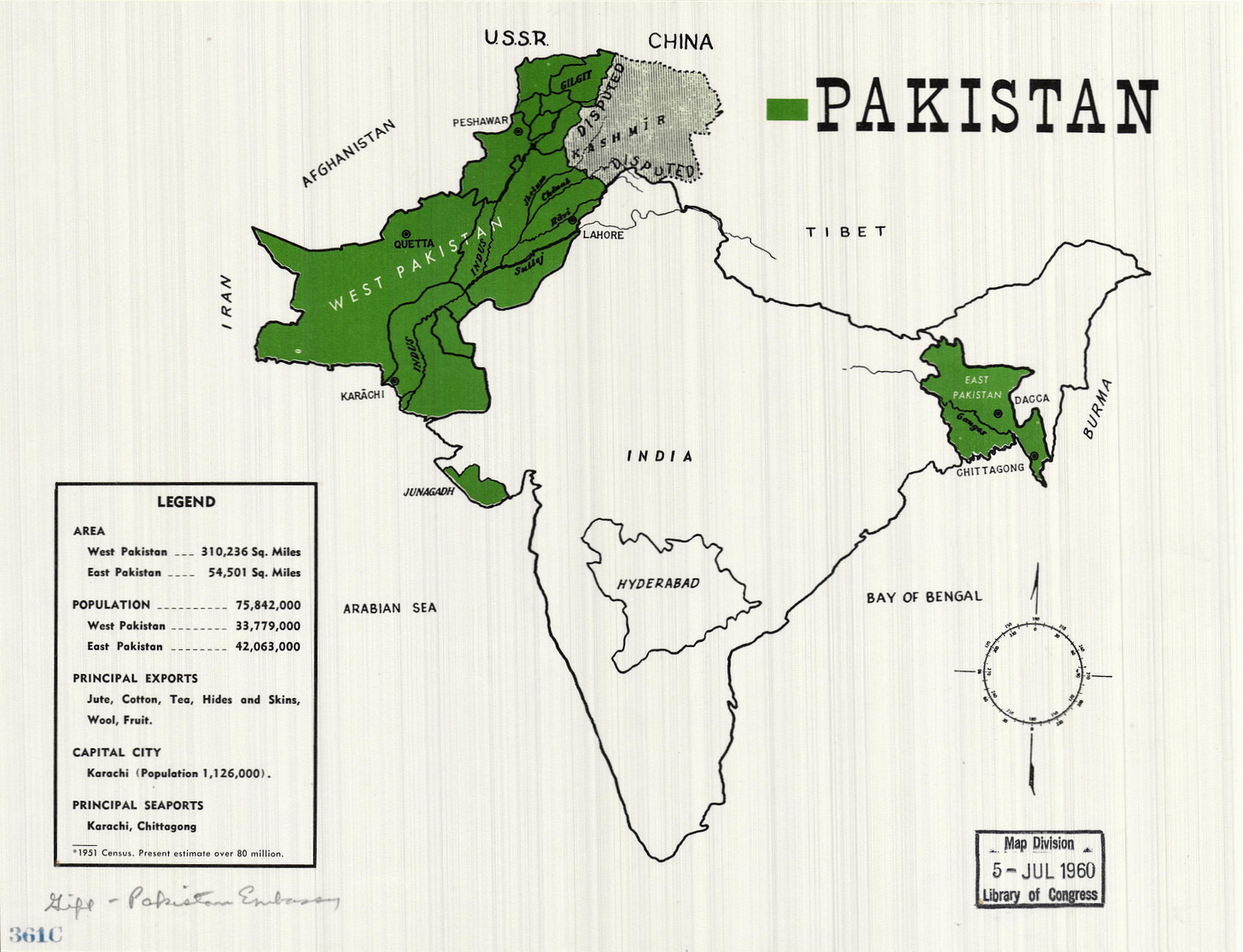

The history of the Bangladeshi garment industry starts when the country was not yet Bangladesh, but Pakistan. Confusingly, at this time Pakistan was a non-contiguous country, the result of British colonial illogic; it consisted of modern-day Pakistan and Bangladesh, but was bisected by the width of India.

The national character of East Pakistan was unsurprisingly distinct from their Western counterparts. There was less appetite for an Islamic theocratic state, and the population’s cultural and national identity was closely tied to their Bengali heritage and language. Politically, soon-to-be-Bangladesh was a more secular and progressive society, and had endured the two decades since Partition as the weaker half in the Pakistani whole, subject to a long line of (West) Pakistani rulers.

Bangladesh’s trajectory towards independence was marked by a bloody war, an all too familiar experience in the canon of postcolonial statehood. The nationalist guerrilla forces, later supported by India and the Soviet Union, rose up in response to the genocide of Bengalis perpetrated by the Pakistani military, whose violent attempts to crush the independence movement only inspired greater resistance. After a campaign involving a great deal of popular participation in armed warfare, the (West) Pakistani forces eventually laid down arms in Dhaka, and Bangladesh became an independent state.

At this juncture, the new government embarked on a program of nationalisation, and attempted a series of land reforms. Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, the prime minister and president of Bangladesh, had a fraught - and short - tenure. It was plagued by famine, cyclones, the inheritance of war-torn cities, a vast influx of repatriating Bengalis, and ended abruptly with the assassination of him and his family at their home in 1975. His nationalisation of industry (including textile production) and extensive land reform spooked the elite classes, as did his decision to replace political plurality with a one-party state.

The power vacuum left by his assassination eventually led to the installation of several military juntas, figure-headed in the late 70s by Major General Ziaur Rahman (Zia), and then by General Ershad in the 80s. Their regimes saw Bangladesh undergo another common period of postcolonial statehood; namely, a process of aggressive neo-liberalisation helmed by strongmen, and aided by Structural Adjustment Programs courtesy of institutions like the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. The currency was devalued, trade barriers reduced, and tax breaks were introduced to woo foreign investors.

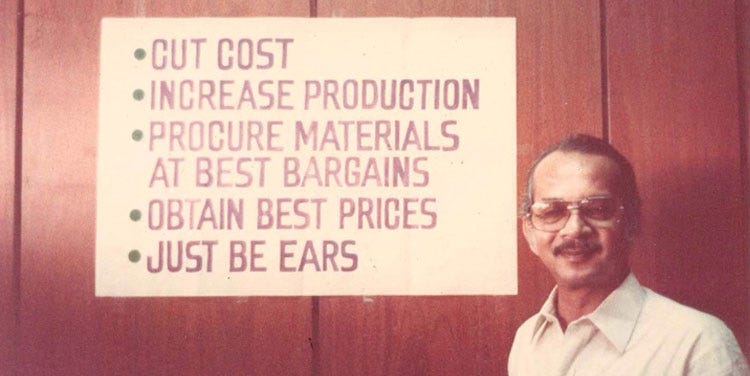

This economic flirtation saw immediate returns in the nascent garment industry. In 1977, 40,000 garments were shipped to Europe by Bangladeshi manufacturers. It was the influence of explorative South Korean business that led to its explosive growth. Daewoo, the once-massive chaebol saw untapped potential in the economy, and sought ties with Desh, a domestic garment manufacturer. The training, expertise, and technology provided by South Korean firms was a vital feed for the germinal garment industry. From here, the exponential growth of the industry began; garment exports went from forgotten child to keystone of the Bangladeshi economy, responsible today for 84%(!) of the nation’s exports.

For some, this was a testament to the efficiencies of the free market, as it was the entrepreneurial class of proto-capitalists who enjoyed the fruit of economic growth. For others, however, the rise of the Bangladeshi garment industry was more nuanced. The conventionally neoliberal policies introduced by the government were crucial in preventing a strong set of labour laws and working conditions from emerging; this encouraged the proliferation of poor conditions that persist into the present. Another factor that is often elided from this success story of globalisation is the large-scale flow of humans (and their cheap labour) that allowed the industry to be globally competitive and attract such vast foreign investment.

The nascent industrialists of the Bangladeshi garment industry recruited middle-class women from across the country’s rural regions. Whilst these women were not from the underclass of Bangladeshi society, their roles in a patriarchal society lowered their status, as they were often not in charge of finances. The work undertaken in garment factories was regarded as ‘feminine’ in character, meaning husbands were less reluctant to allow their wives to migrate (temporarily) to the industrial cities.

On top of the fact that their wages were a pittance - especially compared to those of garment workers in the USA and Europe - women were preferred for their “docility and dispensability” (Kabeer 1994). Whilst this assertion screens the agency and resilience of female garment workers, patriarchal structures have allowed owners to easier manage their workforces and dissuade collective action.

The feminisation of the workforce is a complicated phenomenon. Of course, it can - and should - be argued that economic emancipation for women is a powerful thing. As we will revisit in a few weeks, this novel financial independence can reshape gendered hierarchies, and tangibly improve the freedoms and agency enjoyed by women in traditionally patriarchal societies. However, if the work is persistently low-paid, rife with ill health, and pockmarked with voids in worker rights, then these emancipatory benefits are limited, and exposure to a dangerous labour market raises its own issues.

Five decades on from independence, garment production in Bangladesh has gone from strength to strength. By some distance the nation’s largest export industry, it employs millions and makes up 7% of global garment production. Interestingly, woven garment growth has been slower than knitted counterparts. This is in large part due to the breakneck production turnaround time demanded by global fashion houses, who are rabidly churning out new designs. Whereas Bangladeshi manufacturers have to waste time importing woven fabrics, there is an abundance of domestically produced yarn that allows new orders to be quicker fulfilled.

The years since independence have seen a near-uninterrupted uptick in the heft of the Bangladeshi garment industry. For headline economic figures, such as GDP, employment rates, exports, and so on, the tale is one of bountiful success. But when we turn to the people who make the industry tick - as this series of articles continually aims to - the waters are muddied. The industry has grown considerably, but this growth is not necessarily mirrored by the fortunes of those who sit at the banks of sewing machines and cutting rooms across Bangladesh.

Understanding the history of this industry, which is reliant on patriarchal hierarchies, structural inequalities, and persistently poor conditions is important, so that the role of governments and corporations in perpetuating these conditions is clear. Only when we understand why the fashion industry is so unjust, can we move towards its improvement.

Bibliography

Ahmed, F.E., 2004. The rise of the Bangladesh garment industry: Globalization, women workers, and voice. NWSA journal, pp.34-45.

Berg, A., Chhaparia, H., Hedrich, S. and Magnus, K.-H., 2021. What’s next for Bangladesh’s garment industry, after a decade of growth?, McKinsey & Company. Available at: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/retail/our-insights/whats-next-for-bangladeshs-garment-industry-after-a-decade-of-growth (Accessed: 18 February 2024).

Dhaka Tribune, 2023. Korea wants to develop Bangladesh's infrastructure, proposes 2-policy change. Dhaka Tribune. Available at: https://www.dhakatribune.com/bangladesh/foreign-affairs/323823/korea-wants-to-develop-bangladesh-s (Accessed: 18 February 2024).

Kabir, A.H., 2013. Neoliberalism, policy reforms and higher education in Bangladesh. Policy Futures in Education, 11(2), pp.154-166.

Kabeer, N., 2020. Women’s labour in the Bangladesh garment industry: Choice and constraints. In Muslim Women's Choices (pp. 164-183). Routledge.

Mottaleb, K.A. and Sonobe, T., 2011. An inquiry into the rapid growth of the garment industry in Bangladesh. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 60(1), pp.67-89.

Rahman, S., 2013. Broken promises of globalization: The case of the Bangladesh garment industry. Lexington Books.

Shehabuddin, S.T., 2016. Bangladeshi politics since independence. In Routledge handbook of contemporary Bangladesh (pp. 17-27). Routledge.

Ullah, A., 2015. Garment industry in Bangladesh: an era of globalization and Neo-Liberalization. Middle East Journal of Business, 55(2031), pp.1-13.

Yunus, M. and Yamagata, T., 2012. The garment industry in Bangladesh. Dynamics of the Garment Industry in Low-Income Countries: Experience of Asia and Africa (Interim Report). Chousakenkyu Houkokusho, IDE-JETRO, 6, p.29.

Really informative - looking forward to the rest of the series!