The Aftermath of Rana Plaza

The Rana Plaza collapse was an industrial disaster of uniquely fatal scale. The reaction should have transformed the clothing industry, but instead fell short, and Rana Plaza's tragic legacy lives on.

The Rana Plaza disaster was met with horror, receiving global attention for its unprecedented scale, and the sheer number of casualties from the immediate collapse and the protracted rescue process. As momentum gathered, it became a reckoning event for the global fashion industry, and the 31 Western multinationals implicated in the collapse. For many, the collapse lit the touchpaper for industrial reform, and offered the chance to create a safer future for garment workers around the world. Unfortunately, both the immediate and longer-term responses to the Rana Plaza collapse have fallen short, both for victims of the disaster, and for the industry at large.

Whilst unique in its scale, and inseparable from its specific causes of lax building codes, particularly aggressive employers, and a host of other factors, Rana Plaza was far from an isolated event. It was the latest, and most extreme, of a sustained pattern of industrial accidents in the Bangladeshi garment industry. In 2005, 64 garment workers had died, and a further 80 were injured, when the Spectrum factory collapsed. The following year, the Phoenix Garments factory collapsed, and 22 more workers were killed.

And in late 2012, a mere five months before Rana Plaza, and only a few miles across Dhaka, the Tazreen Fashion factory took the lives of 112 workers when it became engulfed in flames. In the three years after Tazreen, 84 more fires have affected the garment sector, injuring close to 1,000 more workers.

In isolation, any one of these incidents would seem sufficiently deadly to encourage some introspection from the global fashion industry, or at least from the Bangladeshi government. Tolerating a certain ‘level’ of industrial accident sets a dangerous precedent, and is a damning indictment of fashion’s biggest players that so many disasters were allowed to take place before action was taken.

Unlike these lesser-known industrial accidents, Rana Plaza was simply too big, and too deadly, to brush under the carpet. It brings to mind the recent case of ITV’s Mr Bates Vs The Post Office, the outraged reaction to which finally catalysed a government response to a longstanding scandal. It is plausible that without such a high death toll, Rana Plaza wouldn’t have garnered the media attention it did, nor would it have sparked the reaction it did.

But what exactly were the changes that Rana Plaza spurred? Forgive the use of ungainly legislative language, but the disaster brought about the creation of: the National Tripartite Plan of Action; United States Trade Representative Plan of Action; and the European Union Sustainability Compact. Each contained a litany of steps intended to regulate and safeguard the industry, although it is notable that the USA’s contribution was not legally binding, thus protecting domestic clothing producers like Walmart.

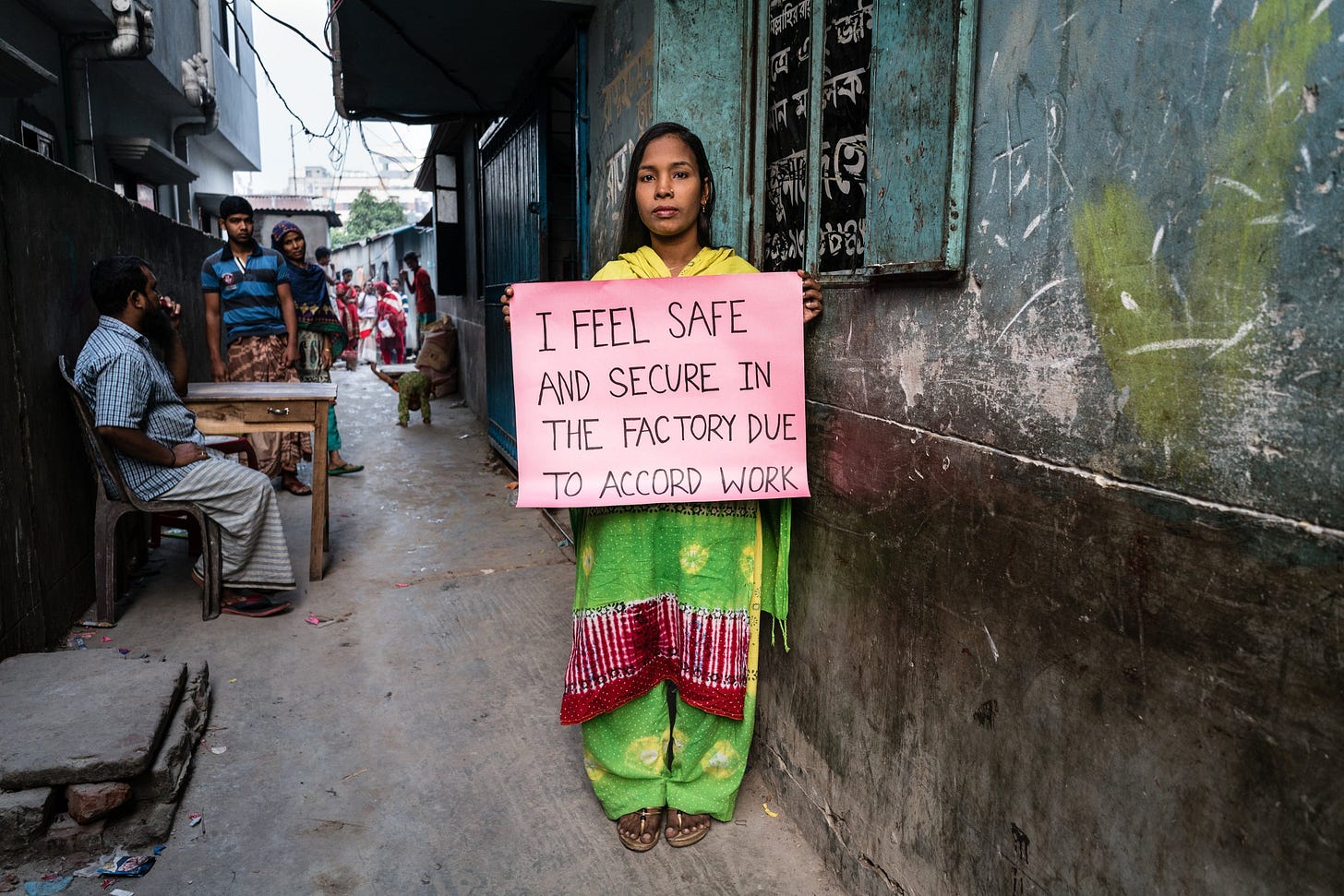

Most important was the Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh. Thankfully, it is known simply as ‘the Accord’. The Accord was hailed as a success in regulatory and corporate efforts to enhance worker safety, and with good reason. According to a comprehensive study on the post-Rana Plaza industry, the Bangladeshi government recruited nearly 400 new inspectors, who had examined 1,250 factories by March 2015. The inspections included analysis of building materials among other checks, and led to the immediate closure of dozens of factories, potentially averting future disasters.

However, the Accord is by no means an unqualified success. Many factories outside of the jurisdiction of large institutions like the Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers & Exporters Association (BGMEA) slipped through the inspection process, and may continue to operate. There has also been resistance from the BGMEA - the most important institution in the industry - and the Bangladeshi state. Close relationships between politicians and owners have allowed many regulatory laggards to escape scrutiny from already lax rules. It was only tenacious, persistent public activism that extended the safer practices into perpetuity, after the Accord’s 5-year lifespan expired.

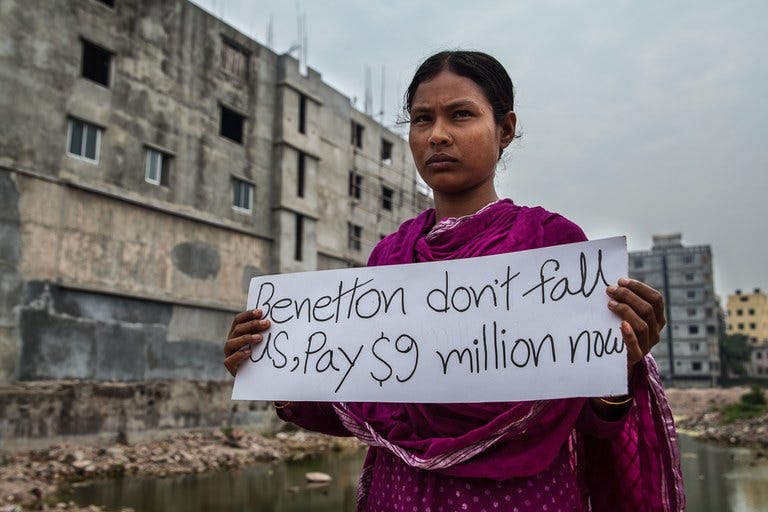

Another point of friction in the post-Rana Plaza landscape is the reluctance of international fashion houses to play ball. As alluded to, many companies denied or distanced their connections to factories in the Plaza, hiding their accountability behind a firewall of PR. In fact, Walmart’s feigned ignorance was the same tactic they had deployed after the Tazreen fire the previous year, where the company’s defence was that they couldn’t possibly have kept track of all the outsourced and subcontracted suppliers they use. Tazreen’s aftermath had also seen the clothing producers lobby against union-led calls for safer, better regulated workplaces.

Amongst the worst offenders is the Children’s Place, an American producer of child and babywear. The company's refusal to acknowledge its role in Rana Plaza was egregious, and added insult to injury when the firm eventually contributed a paltry $450,000 to the victims’ fund. To put it into context, this money (to be split between thousands of victims and bereaved families), amounted to about 1/40 of the CEO’s yearly income.

Plainly, a broad brushstroke analysis of Rana Plaza reveals an unsatisfactory response: one that protected Western retailers’ reputations, and also their revenues, whilst failing to ensure the regulatory overhaul clearly needed to protect Bangladeshi workers. But what of the casualties of the collapse, of the families torn apart, of the workers whose lives were permanently changed?

Compensation packages from the fashion world to the victims and their families were never made legally binding. For many of the surviving victims, the collapse had spelled the end of a career. Chronic physical injuries limited their abilities to rejoin a physically-demanding industry. In a workplace where shifts can last up to 16 hours, with inadequate breaks and repetitive manual labour, compensation should have covered future earning losses on top of the immediate damages of the event. The following are quotes taken from a series of interviews of survivors by the researcher Humayan Kabir:

“I lost my right hand by the collapse. Now, I depend on my left hand to do anything . . . I cannot explain how I feel about losing my hand.”

“As I am not capable to do work now, we are living in extreme poverty . . . I wish to have economic help hand to hand. And I demand to receive the pension for the rest of my life.”

Psychological traumas also impacted future employment opportunities, with many afraid to revisit the ostensibly-unchanged conditions of the industry. Two years after the event, 83% of the survivors remained unemployed. PTSD, anxiety, sleep disorders, and suicidal ideation have all been observed in survivors of the disaster:

“Today I think it was better if I was found dead during the collapse, surviving with different health complexities along with the jobless, life has become meaningless for me.”

“I dream bad dreams very often and become scared still today if I remember the day of the collapse. I cannot think of working or living in the high rise building as I am frightened of the repetition of the same incident again in my life.”

A particularly tragic outcome of the disaster - exacerbated by the disproportionately female workforce of the Rana Plaza garment factories - is how it affected some victims’ childbearing abilities:

“I was pregnant and my child had died in my womb due to the fall of a beam on my belly/abdomen. According to the doctor, I will not be able to conceive a baby anymore. I cry often thinking about my unborn baby.”

“The doctor confirmed me that I will not be able to give birth because my belly/abdomen got seriously injured by the collapse. This incident is the saddest part of my life. I do not find any meaning of my life . . . .”

These life-changing, traumatic events of the collapse demand a lot more than financial compensation, but the meagre offerings from Western corporations undershot this low bar. According to one study, only 2.2% of respondents confirmed they had received all of the compensation promised to them. A lack of formal process meant that, even when large sums of money were donated, it was unlikely to reach the victims.

Even medical treatment became nigh-on-inaccessible. Victims that had initially received treatment and attention from NGOs and authorities later reported being turned away from hospitals by confused doctors. Others slipped through the net, and were not contacted or offered medical care or compensation at all.

The role of NGOs in the restitution process was nebulous. Western retailers were much more comfortable giving money to the NGOs, who were then supposed to assist the victims. Whilst a charitable view could see this as corporations relying on the expertise of specialist organisations, this third-party mechanism allowed retailers to distance themselves from the compensation process and share the reputational ‘glow’ of NGOs. In this sense, these elite NGOs - themselves distrusted by the victims - erode worker rights by shielding large corporations from reputational damage. Ennobling these NGOs as the sole arbiter of compensation also harmed workers, as is clear from the lack of support reported by victims.

Previously, we focussed on the collapse of the Rana Plaza complex, and the conditions that made such a deadly event more likely. This time, we have seen that the collapse captured the attention of a global audience, and has brought about some much-needed reform. Recently, the International Labour Organisation has begun a pilot scheme to pay a fixed income to victims, which - if successful - could support those affected. However, the changes to date are demonstrably insufficient to safeguard workers into the future, and oppressive, poorly-paid conditions persist.

Most importantly, many of the victims continue to be plagued by the disaster and its consequences. For them, Rana Plaza didn’t just take place over a day, or the weeks spent under rubble. Instead, the disaster is ongoing, not just in the form of lasting physical and psychological injuries that it caused, but also in the continued failure of those at fault to properly redress their role in the collapse.

Bibliography

Aclea, L., 2022. Rana Plaza: Nine Years On. Traid. Available at: https://www.traid.org.uk/rana-plaza-nine-years-on/

Akhter, S., 2014. Endless misery of nimble fingers: The Rana Plaza disaster. Asian Journal of Women's Studies, 20(1), pp.137-147.

Ansary, M.A. and Barua, U., 2015. Workplace safety compliance of RMG industry in Bangladesh: Structural assessment of RMG factory buildings. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 14, pp.424-437.

Barua, U., Wiersma, J.W.F. and Ansary, M.A., 2021. Can rana plaza happen again in Bangladesh?. Safety science, 135, p.105103.

Chowdhury, R., 2017. The Rana Plaza disaster and the complicit behavior of elite NGOs. Organization, 24(6), pp.938-949.

Clean Cloth Campaign, 2013. ‘Still Waiting’.

Clean Cloth Campaign, 2015. ‘Who Has Paid and Who is Dragging Their Heels’

Fitch, T., Villanueva, G., Quadir, M.M., Sagiraju, H.K. and Alamgir, H., 2015. The prevalence and risk factors of Post‐Traumatic Stress Disorder among workers injured in Rana Plaza building collapse in Bangladesh. American journal of industrial medicine, 58(7), pp.756-763.

Kabir, H., Maple, M., Islam, M.S. and Usher, K., 2019. The current health and wellbeing of the survivors of the Rana plaza building collapse in Bangladesh: a qualitative study. International journal of environmental research and public health, 16(13), p.2342.

Matthews, A., 2015. Sack, cloth and ashes. Al Jazeera. Available at: http://projects.aljazeera.com/2015/08/rana-plaza/childrens-place.html

Motlagh, J., 2016. Rana Plaza, three years later: Who has paid? Al Jazeera. Available at: https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2016/9/7/rana-plaza-three-years-later-who-has-paid

Press, A., 2021. Big brands rejected Bangladesh factory safety plan, The Mercury. The Mercury. Available at: https://www.pottsmerc.com/2013/04/26/big-brands-rejected-bangladesh-factory-safety-plan/

Thanks for another well researched and revelatory article. The inclusion of the first hand testimony was particularly moving.

This makes for difficult reading. Well done for honouring the victims by keeping the story alive in your well-researched and well-written article. The complacency and lack of accountability from familiar global fashion brands is shocking, indeed sickening. I hope that eventually, the plight of these workers is eased somewhat, but I have little faith.